Most of us prepare traditional, time-honored, often-complicated recipes during the holidays as a tribute to the slavish hours put in by our mothers in years gone by. These elaborate dishes are the culinary equivalent of a photo album, honoring not only our ancestors but what they ate around a shared table. But what if we were “given permission” by today’s star chefs to keep-it-simple? Then maybe we would! During the holidays, when too many people are in the kitchen, too many meals to prepare, and expectations that are exalted, this approach allows the harried cook to have as much fun as their guests. The idea? To fulfill the promise of abundance without the burden.

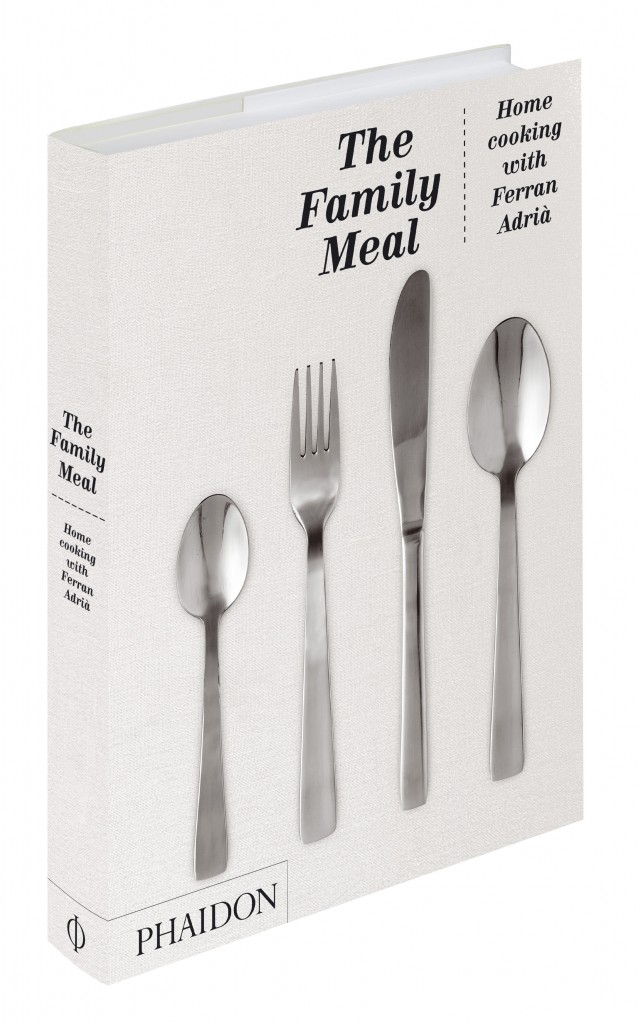

This year, some of the world’s most revered chefs inadvertently satisfy this need in new cookbooks coming out this season. Many of the most illustrious -- Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Marc Vetri, Daniel Humm, Heston Blumenthal, and Ferran Adria – share some of their simpler ideas in titles such as “Home-Cooking with Jean-Georges,” “Heston Blumenthal at Home”, Vetri’s “Rustic Italian Food,” Adria’s “The Family Meal,” and Jacob Kenedy’s (from London’s hot restaurant Bocca), approachable tome, “Bocca.” Even Daniel Humm, in his uber-sophisticated book “11 Madison Park,” presents some do-able, holiday recipes. If you look hard enough, you will find them. I have had the pleasure of browsing these inspiring books and found recipes that meet "radically simple" standards: not too many ingredients, simple procedures, with an existential trade-off of time and effort. These are the dishes that one craves during the busiest time in our lives. Sporting the colors and flavors of the season while they infuse the spirit of tradition with a shot of modernity. Crafting a holiday meal from these collective works would look something like this:

Most of us prepare traditional, time-honored, often-complicated recipes during the holidays as a tribute to the slavish hours put in by our mothers in years gone by. These elaborate dishes are the culinary equivalent of a photo album, honoring not only our ancestors but what they ate around a shared table. But what if we were “given permission” by today’s star chefs to keep-it-simple? Then maybe we would! During the holidays, when too many people are in the kitchen, too many meals to prepare, and expectations that are exalted, this approach allows the harried cook to have as much fun as their guests. The idea? To fulfill the promise of abundance without the burden.

This year, some of the world’s most revered chefs inadvertently satisfy this need in new cookbooks coming out this season. Many of the most illustrious -- Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Marc Vetri, Daniel Humm, Heston Blumenthal, and Ferran Adria – share some of their simpler ideas in titles such as “Home-Cooking with Jean-Georges,” “Heston Blumenthal at Home”, Vetri’s “Rustic Italian Food,” Adria’s “The Family Meal,” and Jacob Kenedy’s (from London’s hot restaurant Bocca), approachable tome, “Bocca.” Even Daniel Humm, in his uber-sophisticated book “11 Madison Park,” presents some do-able, holiday recipes. If you look hard enough, you will find them. I have had the pleasure of browsing these inspiring books and found recipes that meet "radically simple" standards: not too many ingredients, simple procedures, with an existential trade-off of time and effort. These are the dishes that one craves during the busiest time in our lives. Sporting the colors and flavors of the season while they infuse the spirit of tradition with a shot of modernity. Crafting a holiday meal from these collective works would look something like this:

Jean-Georges’ Crab Toast with Sriracha Mayonnaise Heston Blumenthal’s Creamy Leek and Potato Soup Daniel Humm’s Almond Vinaigrette on a salad of endive, watercress & Roquefort Jacob Kenedy’s Duck Cooked Like A Pig Ferran Adria’s Catalan-style Turkey Legs Heston Blumenthal’s Slow-cooked Rib of Beef (1 ingredient/new technique) Daniel Humm’s Extreme Carrot Puree (two ingredients) Marc Vetri’s Fennel Gratin Heston Blumenthal’s Beetroot Relish Jean-George’s Fresh Corn Pudding Cake Marc Vetri’s Olive Oil Cake Heston Blumenthal’s Potted Stilton with Apricot, Onion & Ginger Chutney

Some of the above tomes are intimidating indeed. But if you are lucky to get any of these books as holiday gifts, you might have fun looking for radically simple recipes to call your own. And before too long, as lights alight on Menorahs and Christmas trees everywhere, look no further than here for this year's radically favorite holiday dishes, including some of my own.