When I was 19 years old, and a student at Tufts University, I got a phone call from my mother who told me about a fascinating man she’d heard on the radio that day. He was Hungarian (as was my mother), cultured and worldly, who knew much about food and dining, and had an interesting job. "He is a restaurant consultant!" she exclaimed, "Maybe that's something for you to think about. He has his own company and creates restaurants all over the world. And he loves a good dobos torte!" Although at that time I was consumed by my passion for food and restaurants, had already been a bartender at 16 (I was tall for my age), had waitressed at a Viennese pastry shop in Harvard Square, and worked in the kitchens at The Harvest restaurant, I knew nothing about this fascinating career choice. I was on track, at that time, to become a psychologist (with a double major in psychology and education.) But as life would have it, I became a restaurant consultant, and also the companion to Jenifer Harvey, the day that George Lang fell in love with her, when he took us on a tour of the Culinary Institute of America, many years ago. On the way back to the city, I rode in the front seat with Mr. Ryan, the chauffeur, while George and Jennifer talked shop in the back. What a time it was! A time of innocence, and confidences.

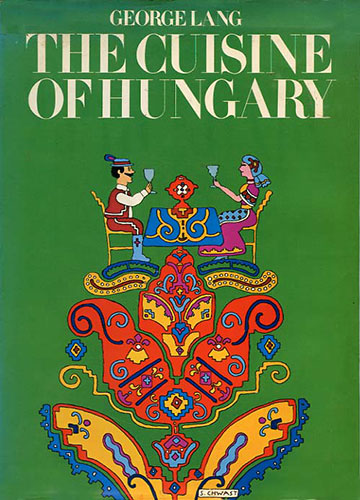

George was one of the most interesting men I would ever know. Brilliant, urbane, cultured, a story-teller, clever, I believed he felt his role in daily life was to amuse and ignite the imagination of others. You never left scratching your head with his worldly references, instead you wanted to scratch his. He was, for all his might, adorable. A brilliant musician whose best friend was the cellist Janos Starker, I ran out to buy an album of Starker's, and tried to learn what I could. I was also a cellist and longed to have that connection to George. George's knowledge of food, wine, history, culture, music, the arts, the art of dining, the art of cooking, was legendary (and very well expressed in William Grimes' tribute to George in yesterday's New York Times), but for me he represented, for awhile, the soul of a generation of Hungarians who were lucky enough to flee during the Holocaust (while sadly much of his family, and mine, and thousands of others did not.) I grew up with George's encyclopedic cookbook in my mother's kitchen. It was the benchmark for tastes and flavors my mother had remembered, but more importantly, it was the conduit to a past I would never know. We thought of George every time we ate a bowl of cabbage and noodles, went out to Mrs. Herbst in search of cabbage strudel, or ventured to Cafe des Artistes for a special celebration. It was one of my parents' favorite places. I loved going just to eat the hard-boiled eggs at the bar. It was "so George." In my own small way, I was a bit of a disciple. Whatever George did, I wanted to eat thereof.

When I was 19 years old, and a student at Tufts University, I got a phone call from my mother who told me about a fascinating man she’d heard on the radio that day. He was Hungarian (as was my mother), cultured and worldly, who knew much about food and dining, and had an interesting job. "He is a restaurant consultant!" she exclaimed, "Maybe that's something for you to think about. He has his own company and creates restaurants all over the world. And he loves a good dobos torte!" Although at that time I was consumed by my passion for food and restaurants, had already been a bartender at 16 (I was tall for my age), had waitressed at a Viennese pastry shop in Harvard Square, and worked in the kitchens at The Harvest restaurant, I knew nothing about this fascinating career choice. I was on track, at that time, to become a psychologist (with a double major in psychology and education.) But as life would have it, I became a restaurant consultant, and also the companion to Jenifer Harvey, the day that George Lang fell in love with her, when he took us on a tour of the Culinary Institute of America, many years ago. On the way back to the city, I rode in the front seat with Mr. Ryan, the chauffeur, while George and Jennifer talked shop in the back. What a time it was! A time of innocence, and confidences.

George was one of the most interesting men I would ever know. Brilliant, urbane, cultured, a story-teller, clever, I believed he felt his role in daily life was to amuse and ignite the imagination of others. You never left scratching your head with his worldly references, instead you wanted to scratch his. He was, for all his might, adorable. A brilliant musician whose best friend was the cellist Janos Starker, I ran out to buy an album of Starker's, and tried to learn what I could. I was also a cellist and longed to have that connection to George. George's knowledge of food, wine, history, culture, music, the arts, the art of dining, the art of cooking, was legendary (and very well expressed in William Grimes' tribute to George in yesterday's New York Times), but for me he represented, for awhile, the soul of a generation of Hungarians who were lucky enough to flee during the Holocaust (while sadly much of his family, and mine, and thousands of others did not.) I grew up with George's encyclopedic cookbook in my mother's kitchen. It was the benchmark for tastes and flavors my mother had remembered, but more importantly, it was the conduit to a past I would never know. We thought of George every time we ate a bowl of cabbage and noodles, went out to Mrs. Herbst in search of cabbage strudel, or ventured to Cafe des Artistes for a special celebration. It was one of my parents' favorite places. I loved going just to eat the hard-boiled eggs at the bar. It was "so George." In my own small way, I was a bit of a disciple. Whatever George did, I wanted to eat thereof.

I loved his restaurant "Hungaria" in midtown with its whimsical "salami tree." I was ecstatic to celebrate my 40th birthday at the ultra-glamorous Gundel in Budapest on New Year's Eve, eat the food of the women at Bagolyvar next door, and try to find the cafe in the opera house that George had a hand in. Instead we wound up eating, unwittingly, with the cast in their garb, in the employee cafeteria! Once, George asked me a question to which he had forgotten the answer. I said, "Alkermes, George." That's the answer." (He wanted to be reminded of the red bitter aperitif used in Italy to moisten cake.) It was George who taught me about the wonderful, and esoteric, cheese from Switzerland called "tete de moines" (the monk's head which needed a special apparatus for shaving off shards that looked like fans...or butterflies.)

I learned from George to be curious, open, and take chances. He was always supportive. He came to the opening of The Cafe I created at Lord & Taylor in the early 1980's and told me to read the work of Helen Corbitt (the woman who created the famous Zodiac dining room in Neiman Marcus in Dallas.) He came to Lavin's -- one of the city's culinary hot spots in those days -- to sample the menu I created. He brought James Beard with him to have lunch with me there. He loved the "Carpaccio Gold" and the new spin I put on familiar dishes. He also loved that we had an all-women kitchen, I believe, one of the city's first. We drank Bulls Blood together (Egri Bikaver -- one of Hungary's most famous wines) and much later sampled some of the wonderful wines he was producing from his vineyards in Hungary. And one day, George called and asked me to come work with him. It was the same week I began to work with Joe Baum, George's dear colleague. George said that's where I should stay.

George Lang emanated brilliance. Whimsy. A life of the mind and of the senses. He even invented a few of his own.