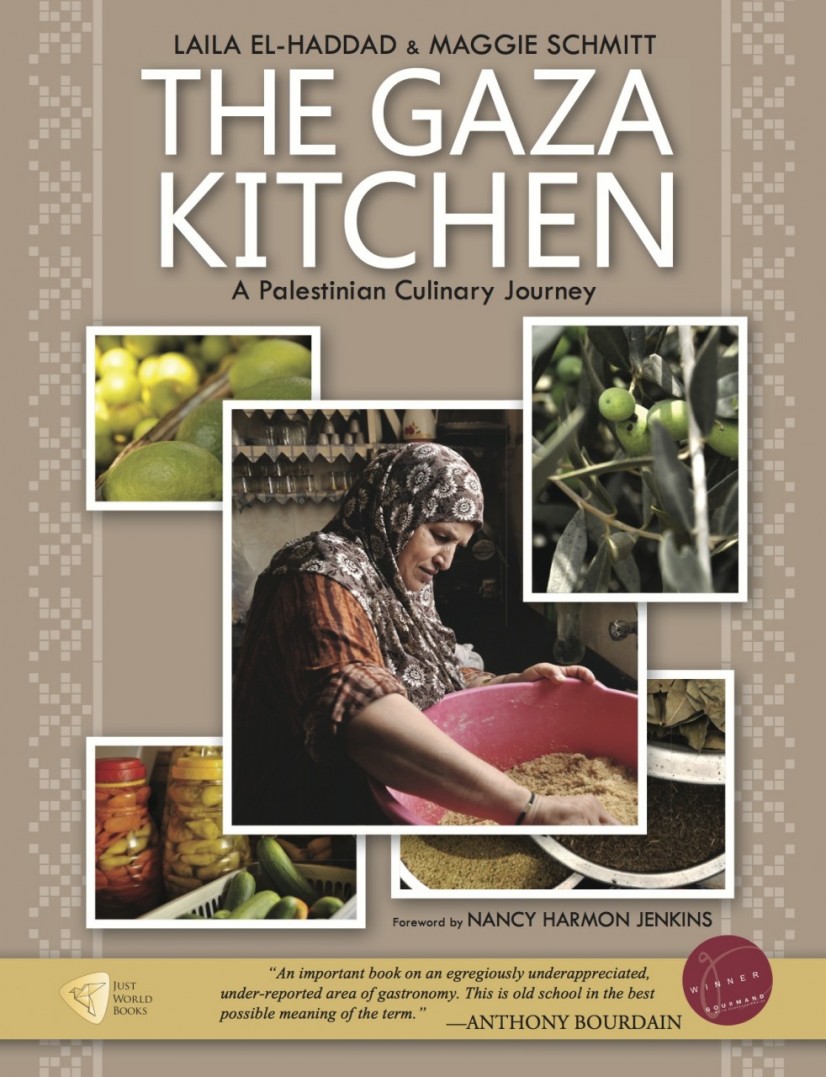

It was with an open mind and a touch of sadness that I read the riveting, and sometimes provocative, new cookbook, The Gaza Kitchen, written by Laila El-Haddad and Maggie Schmitt. I had the pleasure of meeting Ms. El-Haddad at her book party launch last month in New York at the sublime restaurant ilili - whose Lebanese cuisine is a distant cousin to the flavors, aromas, and politics found in the Gazan kitchen. Ms. El-Haddad, who is a social activist, blogger and author of Gaza Mom: Palestine, Politics, Parenting, and Everything In Between, felt like an old friend. After all, there was a time, long ago, when it was possible for Jews to have Palestinian friendships in the Old City of Jerusalem and share meals, and the culinary history, which has existed between us for thousands of years. Now there is a wall, both literal and metaphoric, that shields us from the realities of everyday existence in Gaza, where home kitchens are prey to the exigencies of conflict and deprivation: sporadic electricity, unaffordable ingredients that were once kitchen staples, and the rationing of food and fuel.

While I know the food of Israel well, having served as the unofficial spokesperson for Israel's food and wine industry for years, and also as one of a delegation of "Four Women Chefs for Peace" on a culinary mission to Israel in 1996, I was fascinated to learn about the cuisine of Gaza, a tiny strip of land (25 miles long and 2-1/2 to 5 miles wide) sandwiched between the desert and the sea. What immediately jumped out was the presence of fresh dill and dried dill seed, the use of fiery hot chilies, and a totally new ingredient to me "red tahina."

It was with an open mind and a touch of sadness that I read the riveting, and sometimes provocative, new cookbook, The Gaza Kitchen, written by Laila El-Haddad and Maggie Schmitt. I had the pleasure of meeting Ms. El-Haddad at her book party launch last month in New York at the sublime restaurant ilili - whose Lebanese cuisine is a distant cousin to the flavors, aromas, and politics found in the Gazan kitchen. Ms. El-Haddad, who is a social activist, blogger and author of Gaza Mom: Palestine, Politics, Parenting, and Everything In Between, felt like an old friend. After all, there was a time, long ago, when it was possible for Jews to have Palestinian friendships in the Old City of Jerusalem and share meals, and the culinary history, which has existed between us for thousands of years. Now there is a wall, both literal and metaphoric, that shields us from the realities of everyday existence in Gaza, where home kitchens are prey to the exigencies of conflict and deprivation: sporadic electricity, unaffordable ingredients that were once kitchen staples, and the rationing of food and fuel.

While I know the food of Israel well, having served as the unofficial spokesperson for Israel's food and wine industry for years, and also as one of a delegation of "Four Women Chefs for Peace" on a culinary mission to Israel in 1996, I was fascinated to learn about the cuisine of Gaza, a tiny strip of land (25 miles long and 2-1/2 to 5 miles wide) sandwiched between the desert and the sea. What immediately jumped out was the presence of fresh dill and dried dill seed, the use of fiery hot chilies, and a totally new ingredient to me "red tahina."

Red tahina, made from roasted sesame seeds, is to Gaza what pesto is to Genoa. It is virtually impossible to get it anywhere and I have asked a friend from Israel to try to find some and bring it to me when she comes to New York at the end of the month. How to use it if you can't find it? The authors suggest adding a bit of dark sesame oil to the more familiar blond tahina to approximate the taste in several of the book's recipes.

The cuisine of Gaza is Palestinian (home to 2 million people) "with its own sense of regional diversity," according to author and historian, Nancy Harmon Jenkins, who wrote the forward to the book. In Gaza, she points out, stuffed grape leaves are uniquely flavored with allspice, cardamom, nutmeg and black pepper, and that chopped chilies, both red and green, and verdant fresh dill make Gazan falafel both personal and unusual.

Food there, no less than here, is a passionate subject. The cooks at home are always women while the cooks in restaurants and outdoor stalls are always men. But it is the zibdiya that unites them in the preparation of their lusty cuisine. According to the authors, "a zibdiya is the most precious kitchen item in every household in Gaza, rich or poor." It is simply a heavy unglazed clay bowl accompanied by a lemonwood pestle used for mashing, crushing, pounding and grinding. Made from the rich red clay of Gaza, in larger forms they are also used as cooking vessels.

Their cuisine may lie at the intersection of history, geography and economy, but in The Gaza Kitchen, one is made acutely aware of how geo-political struggles find themselves revealed in a single dish. It's hard not to swoon over the description of the "signature" dish of Gaza called sumagiyya, a sumac-enhanced meat stew cooked with green chard, chickpeas, dill, chilies, and red tahina, or not to be curious about fattit ajir, a spicy roasted watermelon salad tossed with tomatoes, torn bits of tasted Arab bread, and a lashing of hot chilies and yes, fresh dill. It is a repertoire of dishes that feel like a secret...but no longer.

Now only if there was a recipe for peace. One can always hope.