Ivory-hued tahina (also spelled tahini) is everywhere. Red tahina is not.

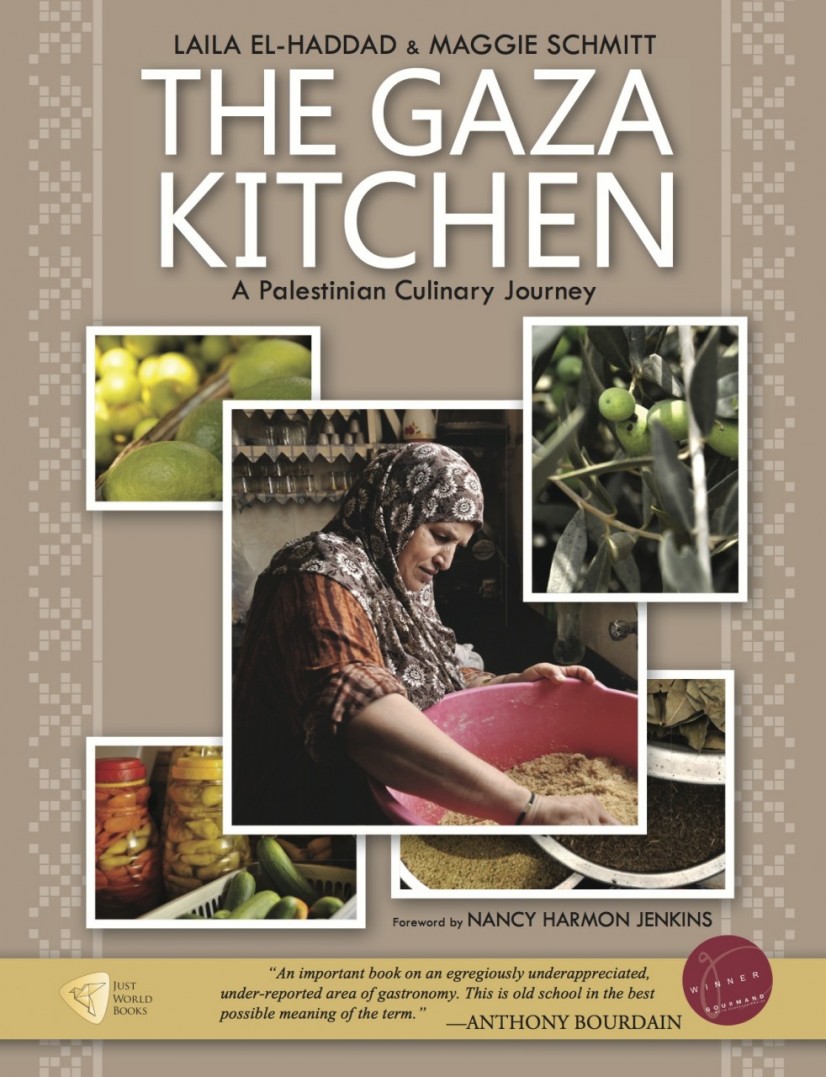

I first encountered the brickish-red tahina in the fascinating cookbook, The Gaza Kitchen, a gift from a Palestinian friend, who referred to it as “the very great Gaza specialty.” In Gaza, where a unique twist of Arab cuisine includes fresh dill and chilies, it is red tahina that lubricates many of their most noteworthy recipes. It’s a key ingredient in the area’s most famous dish – sumagiyya, a stew made with beef or lamb with sumac, chard, chickpeas, dill, and chilies. And it’s an important flavor in salata maliha, which translates as “beautiful salad,” a toss of old bread, tomatoes and cucumbers, and in Gaza-style potato salad, where red tahina is drizzled over boiled and fried potatoes tossed with a garlic and lemon dressing.

With dishes like these to entice me, is it any wonder that on a recent trip to Israel I felt compelled to search for red tahina, determined to carry home this highly valued ingredient found almost exclusively in Gaza. Given the burgeoning fascination in the U.S. with Israel’s Arabic-inflected cuisine, I could taste its destiny in our ever-expanding global pantries. Tahina, made from raw, steamed sesame seeds, is a critical component of hummus, which Americans are consuming in stratospheric quantities, so red tahina, I surmised, was something we should know about.

Try finding it in New York City, where we think we can get anything in the world. You cannot. You’ll even have epic difficulty finding it in Jerusalem. My food-obsessed Israeli friends had never even heard of it.

To acquire red tahina, you must know someone who knows someone. It took an hour of explaining, cajoling, pointing, and sweating through the fragrant, serpentine maze of cubbyhole shops that crowd the Old City’s souk to identify someone who might sell the stuff. Then we got a lead – a friendly spice merchant at a far corner of the marketplace wrote a note in Arabic describing the location of an obscure vendor. There was no GPS for the souk, and we ran past his shadowed stall twice before guessing we were there.

Feeling like Indiana Jones, my comrades and I slipped the note to the proprietor, whereupon he disappeared into the back of his shop and silently rematerialized with a jug that looked as if it might contain a genie – or something more exciting than sesame paste. He gave us several tastes, then poured a lava-like substance into white plastic jars. These would be gifts to friends in Tel Aviv who doubted the stuff’s very existence.

The note looked like this:

More ruddy than red, this tahina is fashioned from pounded and pulverized sesame seeds that have been dry-roasted in small batches over direct fire, then processed into an oozing stream of intriguing, earthy complexity. The roasting imparts red tahina with its deep terracotta color and nutty, caramel flavor, in contrast to the more one dimensional flavor of the familiar cream-colored tahina, or black tahina, made from nigella seeds and known in the Arab world as an aphrodisiac.

Hummus is even more seductive when made with this stuff. (Interestingly, Gaza is also known for its rich red clay, which looks a lot like their brick-red tahina.) But since you won’t find red tahina at your local specialty store, you can approximate its taste --but not its unique color, texture, or its rich history – by using Chinese sesame paste (also made from roasted sesame seeds), or by adding ½ teaspoon of dark Asian sesame oil to the more ubiquitous tahina that appears to be everywhere.